Why We Do it

Making Justice addresses learning gaps that disproportionately impact minority youth in Dane County, Wisconsin.

Dane County is home to one of the nation’s widest black/white educational achievement gaps and highest per capita black juvenile arrest and incarceration rates. To better understand our motivations for addressing these inequities, we the makers—teens, peer learners, facilitators, and partnering staff—have shared our reflections on the meaning of Making Justice.

Why we do it interweaves our voices as part of an ongoing dialog that sustains community building within and beyond Making Justice. Check out our Authors page to learn more about the contributors to this curated community article.

Inequity in Madison’s Dane County

Madison is a prosperous city. Residents are more affluent, are less likely to be unemployed, and are better educated than their national counterparts. African American residents, however, fare significantly worse than the larger community in five leading indicators: criminal justice, economic well-being, education, health care, and housing. The State of Black Madison 2008

Recent local and national studies have suggested that Dane County is home to some stunningly wide black/white disparities on several significant outcome measures, especially those relating to the criminal justice system and to educational achievement. Race to Equity 2013.

Madison cannot measure its own progress on race relations. We need to sit at a table with disenfranchised people to get a painful but accurate read on our city from their experiences. I challenge the entire community to become concerned and involved. Justified Anger 2013.

Grant application: Making Justice addresses the nation’s widest black/white educational achievement gap and highest per capita black juvenile arrest and incarceration rate, advancing the Wisconsin Idea that the university should improve people’s lives beyond the classroom. Black Dane County teens are 13 times more likely to be growing up in poverty than their white neighbors. Half will not graduate from high school on time. These disparities contribute to a pipeline of accumulating risk factors that too often ends in the justice system. Although less than nine percent of county youth are black, they represent 43 percent of juvenile arrests, 63 percent of juveniles in detention, and almost 80 percent of youth in the state juvenile correctional facility. Those who matriculate to the adult criminal justice system, which has jurisdiction over all 17-year-olds, face a lifetime of discrimination in employment, housing, education, public benefits, voting and jury rights. In response to these disparities, black community leaders have recommended out-of-school programs for underserved youth and challenged marginalized populations to register their voices and concerns, calling attention to injustice and inequity.

What does Making Justice Mean?

Alan: What does Making Justice mean? What does that mean?

Jesse: It’s kind of loaded. I love the name, but it’s almost like a boast. Like “there’s no way you’re making justice. How dare you say that?” You know what I mean? That would be my first reaction, if anybody told me that they’re making justice…I’d be like “Bullshit. Define that to me.” Because I don’t feel like there’s a very just world that we’re living in right now. So I feel like it’s a very great goal to name it that, I’m okay with it, but that always eats at me a little bit. Because I don’t like to brag. I really like programs to speak for themselves. I never want to have to tell somebody about our program. I want them to experience it and then know what it is and then tell somebody else.

Rob: I will summarize it really simple. How + What = Why. The How is what we have to offer. The What is their experience. And when you put those two things together you get the Why. I think we are there to offer what we have to offer, in our different lanes, in hopes that these kids will latch on to it, to find a better way to make their own justice. To be able to give them another option, that’s justice. And that’s why I work to make justice. You know, because they---I come from a background where we didn’t have a lot of options and I was fortunate that I got the options. So now I’m trying to pay it forward. And the hope is that these kids understand that and make their own justice as they continue to pay it forward.

Faisal: For me it’s a really bold and reactionary title. It’s fairly explicit…you know the kids have got some issues. I’m in there purely for them, they’re brilliant. All they need is time. If you give them time, some of them will go on to do great things, and they will happily look over their shoulder and give back, as a matter of course.

John: I would describe it as a program that provides an opportunity for youth who have had some struggles in their lives. And they haven’t had the opportunity to really figure out a way to express themselves yet. That's really what it's about.

Ed: The common denominator is not the justice system, the link is the struggle, the survival…the inspiration behind people’s work. Because there are some people out there that haven’t gone to court but have gone through some things and this is why they participate. You know what I’m sayin’? There’s not a lot of people that end up in court. There’s a lot of people out there…they just didn’t get caught.

Ben: To me, the purpose and value of Making Justice is that it gets the kids out of their boxes—that they or others build around them—that prevent them from growing. They feel like they’re trapped, that they don’t have a future…they’re stuck in the present. So the Making Justice program allows them the opportunity to expand themselves and to start thinking that they do have ability and talents and value, so they can start moving forward.

Britt: I think it’s providing opportunities for experiential learning that kids wouldn’t typically access on their own. And allowing them to be vulnerable, allowing them to engage in something that maybe they’re already good at, or maybe it’s incredibly challenging. To me, Making Justice means engaging in a process that feels productive and maybe your voice is being heard. Where you’re able to articulate how you’re feeling through whatever you’re participating in. Something that made you feel strong, something that made you feel weak, just an opportunity to engage.

Jesse: The experiential learning is absolutely key in my book. My favorite comment of all time was after a book trailer workshop, when someone wrote on a card “It was great to take a break from learning.” They’d just made a marketing video for a book, and their teacher’s like, “What the…?” But in their head, like I’m envisioning, learning meant someone talking to me in a classroom in a seat and telling me stuff... Not like actively making something and figuring out how to edit things. That one sentence just sums up—that was my childhood too. I hated learning. But really I loved it. I just didn’t like being talked to and expected to memorize and regurgitate on the test.

Dana: I really appreciate the making part. Not just making something, but something that will be treasured.

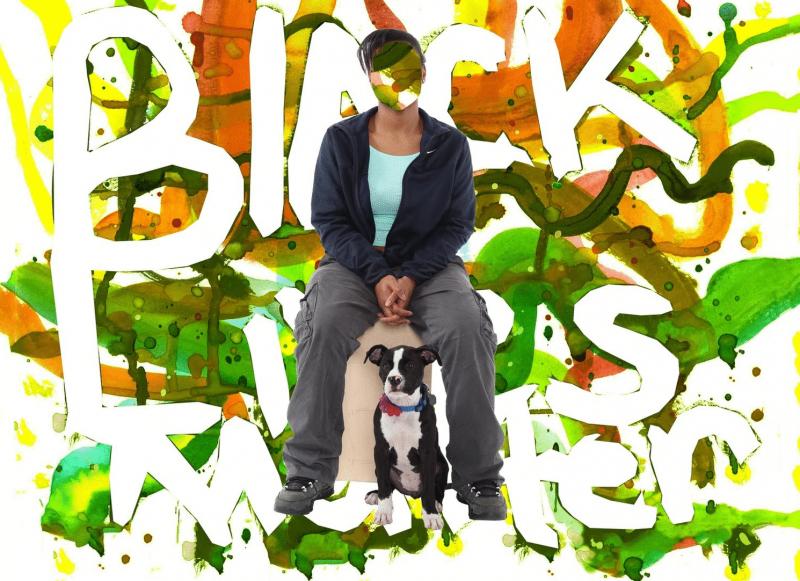

Gerardo: There’s an action component that relates to social justice. Here’s an injustice that’s happening. How do we talk back to that injustice?

Teen: I think it really should be called "restoring justice", right? Because it kinda brings justice back to us. Like, everybody always thinks we are black and got into trouble and so we are bad. But they don't know how much I bite my tongue. If I were back in Africa, I would fight other students for real, but here you go into detention, so I don't even care as long as they don't touch me. You can talk with your freedom of speech but do not ever touch me.

Alan: You know it takes a child to raise a village. That is the time and space we live in today in Madison. The Urban League ain't solving shit, the University ain't solving shit, the police ain't...nobody's going to solve anything other than these kids wanting something different and making justice starting with themselves. Right? Opening this door, and saying “Come in.” To me that is Making Justice.

Andre: It’s an opportunity to expose the community to kids who have struggled, in a different way than they're used to viewing them. A subset of kids that they would have given less value to, to see them differently. And that's an outcome we may not have initially thought about, but maybe one of the most powerful, of really changing the community.

Nancy: We started out focusing on media arts, and addressing learning gaps for kids who’ve had a rough shake. But now I define Making Justice in terms of building community. Too often we put the onus on the kids, that they need to learn certain things, they have a gap. I have a learning gap. The university students I brought into the program had a learning gap. We need to realize the multiple ways that we contribute to injustice. All of us. To learn about building relationships and working with the entire Madison community to address why too many kids are getting caught up in the justice system.

Kay: Making justice began with this disproportionate minority confinement issue, but really it is larger than that. Everybody needs to make justice with your own self, with your family, helping each other. It’s a life-long project. We’re here on this earth to help ourselves become more.

Britt: The connections that are made between the students and the community members in Making Justice are invaluable, and have led to some great and unexpected things. It’s nothing I can replicate as a teacher in the classroom, even if I tried. Even being in the process of becoming Making Justice and stumbling through things changing and taking different paths was a cool process.

Veronica: It’s important, however you frame it, to really point out the fact that the kids came together to give back something beautiful to the community…they did it specifically to give of themselves to the community.